We like stocks that generate high returns on invested capital," Warren Buffett told those in attendance at Berkshire's 1995 annual meeting, "where there is a strong likelihood that it will continue to do so."

"I look at long-term competitive advantage," he later added, "and [whether] that's something that's enduring."

According to Buffett, the economic world is divided into a small group of franchises and a much larger group of commodity businesses, most of which are not worth purchasing. He defines a franchise as a company whose product or service (1) is needed or desired, (2) has no close substitute, and (3) is not regulated. Individually and collectively, these create what Buffett calls a 'moat' - something that gives the company a clear advantage over others and protects it against incursions from the competition. The bigger the moat, the more sustainable, the better it is.

The key to investing is determining the competitive advantage of any given company and, above all, the durability of that advantage. The products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors.

He suggests that buying a business is akin to buying a castle surrounded by a moat. Buffett wants the economic moat around the businesses he buys to be deep and wide to fend off all competition. He goes one step further, noting that economic moats are almost never stable; they're either getting a little bit wider, or a little bit narrower, every day. So he sums up his objective as buying a business where the economic moat is formidable and widening.

As he wrote in his 1994 letter to shareholders…

Look for the durability of the franchise. The most important thing to me is figuring out how big a moat there is around the business. What I love, of course, is a big castle and a big moat with piranhas and crocodiles.

Now, as much important as they are, moats are fairly rare and come from a variety of things, such as brand, intellectual property, scale economies, a regulatory advantage, high customer switching costs, or some sort of network effect.

My goal in this lesson (and the next two) will be to help you develop a systematic way to explain the factors behind a company's moat. We would also understand how you can assess whether a moat is declining or widening.

How Companies Create Value

Ideally, corporate managers try to allocate resources so as to generate attractive long-term returns on investment. Similarly, investors try to buy the stocks of companies that are likely to exceed embedded financial expectations. In both cases, sustainable value creation is of prime interest. Now, what exactly is sustainable value creation?

We can think of it across two dimensions.

Now, the question is - how does a company generate returns in excess of its cost of capital? What are the key value drivers of such excess returns?

If you read Charlie Munger's analysis of Coca Cola in his talk titled Practical Thought on Practical Thought, there are two key drivers of value for any business -

These are the two most important factors (cause) that drive a business's long term excess returns (effect), which ultimately create value for you as a long-term investor. These are also the factors that we would focus on in this series of lessons on 'moats.' Anyways, the second dimension of sustainable value creation is how long a company can earn returns in excess of the cost of capital. Despite the unquestionable significance of this longevity dimension, most investors give it scant attention, while focussed only on identifying moat as of now.

Charlie Munger says…

Over the long term, it's hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns 6% on capital over forty years and you hold it for that forty years, you're not going to make much different than 6% return - even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you'll end up with one hell of a result.

A key implication of Munger's quote is that, in the long run, investors earn only as much money on a company's stock as the underlying business itself earns.

Hence, it pays off well to invest in companies which are able to -

Thus, to really study the subject of "moats," it's important that we ingrain this in our minds that we are trying to also study the "sustainability" of moats. Only then can we work towards identifying businesses that can really create wealth for us in the long run.

This is the way we are going to study the subject of moats over the next three lessons - the first two on identifying the qualitative sources of moats (with a few examples), and the third one using some quantitative analysis to identify moats.

First, Why Moats Matter

Consider how most of us make our purchasing decisions in life. It seems common sense to pay more for something that is more durable. From kitchen appliances to cars to houses, items that will last longer are typically able to command higher prices, because the higher up-front cost will be offset by a few more years of use. For example, Bata shoes cost more than their local counterparts. Prestige or Hawkins pressure cookers will command a higher price than Desco cookers. Samsung mobiles would cost you more than those from Lava.

This very concept applies to the stock market. Durable companies - business that have strong competitive advantages - are more valuable than companies that are at risk of going from hero to zero in a matter of months because they never had much of an advantage over their competition. This is the biggest reason that economic moats should matter to you as an investor - Companies with moats are more valuable than companies without moats.

So, if you can identify which companies have sustainable economic moats, you'll pay up for only companies that are really worth it. This is because such a company, thanks to its moat which protects it against competition, would help it earn a high return on capital (ROE, ROCE), which is one of the most important determinants of returns for you as a shareholder. What is more, these high returns would sustain for a long period of time if the said company is able to sustain its moat.

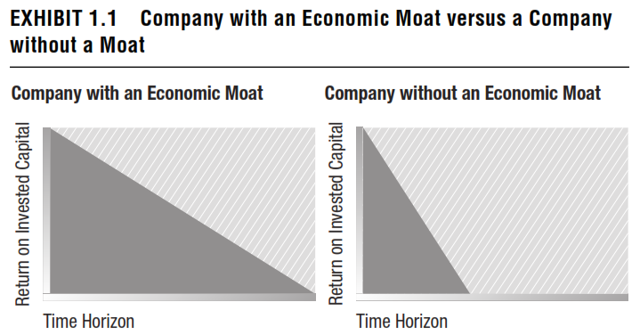

In his brilliant book, The Little Book that Builds Wealth, here is how Pat Dorsey shows the difference between a company with moat and one without…

In the above image, time is on the horizontal axis, and returns on capital are on the vertical axis. You can see that returns on capital for the company on the left side - the one with the economic moat - take a long time to slowly slide downward, because the firm is able to keep competitors at bay for a longer time.

The no-moat company on the right is subject to much more intense competition, so its returns on capital decline much faster. The dark area is the aggregate economic value generated by each company, and you can see how much larger it is for the company that has a moat.

So, a big reason that moats should matter to you as an investor is that they increase the value of companies. Identifying moats will give you a big leg up on picking which companies to buy, and also on deciding what price to pay for them. Now, why else should moats be a core part of your stock-picking process?

Thinking about moats can protect your investment capital in a number of ways. Here are the five key ones -

Overall, if you can see moats where others don't, you'll pay bargain prices for the great companies of tomorrow. Of equal importance, if you can recognize no-moat businesses that are being priced in the market as if they have durable competitive advantages, you'll avoid stocks with the potential to damage your portfolio.

Durability of Moat - Revisiting Mr. Porter

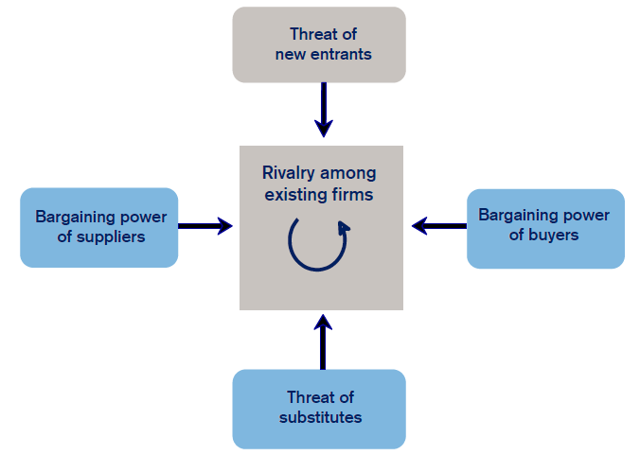

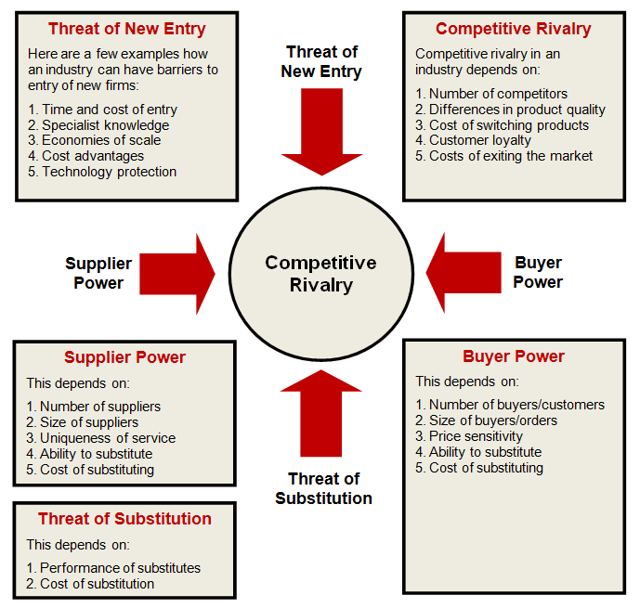

In Lesson #18 on how to analyze an industry and the competitiveness of its constituent companies, we had discussed about Michael Porter's "Five Forces Analysis", which is one of the best ways to assess an industry's underlying structure.

While some investors and analysts employ the framework to declare an industry attractive or unattractive, Porter recommends using industry analysis to understand "the underpinnings of competition and the root causes of profitability."

In fact, an individual company can achieve superior profitability (and thus 'moat') compared to the industry average by defending against the competitive forces and shaping them to its advantage.

When you are studying a company's moat (or whether one has it or not), it's very important to have these five forces in mind when thinking about the resilience or sustainability of that moat.

Use this template as a checklist to identify if a company has a moat that will sustain for a long period of time…

Porter's Five Forces Analysis Template

By thinking about how each force affects its industry, and by identifying the strength and direction of each force, a company can quickly assess the strength of its position and its ability to make a sustained profit in the industry.

As an investor, you can use this framework for assessing whether a specific company has a sustainable moat that can turn it into a profitable investment over the next 10 years or more.

Sources of Economic Moat

After discussing the importance of focusing on identifying moats while analysing business, let me now take you through the key sources of moats - sources that provide a company a sustainable competitive advantage that can help it earn great return on investment and for a long period of time.

For most companies having long-term sustainable moats, one or more of the following characteristics exist -

I will discuss the first two in this lesson, and the remaining two in the next.

Moat #1: Strong Brand Power

Here is something Charlie Munger said in his talk Practical Thought on Practical Thought - as an advice to an imaginary founder of Coca-Cola on how to make it successful in the long run -

…we are never going to create something worth $2 trillion by selling some generic beverage. Therefore, we must make your name, "Coca-Cola," into a strong, legally protected trademark.

The very fact that strong trademarks or brands take a long time to build make them such a strong source of economic moat for a company that have them.

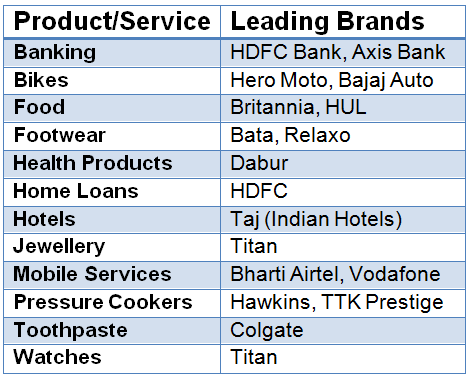

Like, take a look at some of the biggest wealth creators in India over the past few years - Asian Paints (average annual return of 36% during 2001-13), ITC (27%) and HDFC (22%). While the inherent quality of these companies' businesses has helped them considerably in creating value for shareholders all these years, one big reason they have been able to do well is the brand power they command in their respective markets.

Ask a painter about the brand of paint most people prefer, and the choice has been Asian Paints for the past many-many years. Smokers would vouch for ITC's cigarettes. And when it comes to home loans, there has been no bigger brand name than HDFC over the past many years.

Apart from these, there have been many brands in India that have become generic names of the products they sell -

Brands, like patents, trademarks, and licenses, are "intangible assets" whose real value you won't find in a Balance Sheet. And thus they are difficult to assess for most investors. But as economic moats, they all function in essentially the same way - by establishing a unique position in the marketplace. Any company with one of these advantages has a mini-monopoly, allowing it to extract a lot of value from its customers.

Now, here comes a catch when it comes to assuming a "great brand" for a "great business", which is not always true. In fact, one of the most common mistakes investors make concerning brands is assuming that a well-known brand endows its owner with a competitive advantage. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. A brand creates an economic moat ONLY if it increases the consumer's willingness to pay or increases customer captivity.

After all, brands cost money to build and sustain, and if that investment doesn't generate a return via some pricing power or repeat business, then it's not creating a competitive advantage.

Case 1: Tata's Nano

Tata Motors, after much fanfare and marketing spend, launched the "Nano" in 2009. The car was meant to succeed as it was…

But despite all this (cheapness, Tata brand, logical appeal), the brand bombed.

The very "cheapness" with which it was marketed caused its downfall. In fact, this is what Ratan Tata admitted recently - "It became termed as a cheapest car by the public and, I am sorry to say, by ourselves, not by me, but the company when it was marketing it. I think that is unfortunate."

Even the Tatas' original car model - Indica - has been a failure, lagging its peers in terms of design and quality, and despite its 'cheap' price tag. So, despite Tata Motors spending big money on building its car brands, it has not been able to generate much return on its investments, and thus it has failed to create any competitive advantage for itself in the car space.

Case 2: Marico's Sparsh

Leading FMCG company Marico (known for its 'Parachute' brand of hair oil) launched a baby soap named "Sparsh" in 2006. The move originally seemed like a marketing masterstroke as there was only one recognized brand (Johnson & Johnson) in such a huge market as India.

In fact, Marico used the brand equity of its 'Parachute' brand for introducing the product in the market. But the move (and the product) did not succeed despite Marico spending a lot of money on promoting the brand. The company failed to realize that mothers would not try out a new brand of soap on their babies. It had to ultimately withdraw the brand after two years of its launch.

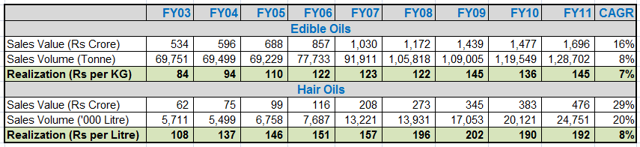

This is the same Marico that has created tremendous value for shareholders through its edible oil (Saffola) and hair oil (Parachute) businesses. See this table that shows how the company has not just constantly grown its volume sales of oils, but also the unit prices (realization per unit) over the years.

During this period, the company has also improved its EBIT margin from 7% in FY03 to 12% in FY13, suggesting that even its profit per unit sold has improved over these years.

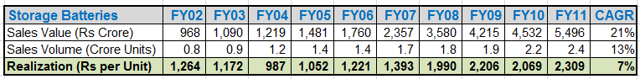

Now look at the numbers from Exide, India's leading car battery manufacturer. As you can see from the table below, not only has the company grown its unit sales consistently during the period FY02 to FY11, even its realization per unit has risen gradually. What is more, the net profit per unit increased from Rs 80 in FY02 to Rs 210 in FY11.

These - Marico and Exide - are just a couple of examples of 'moat' businesses that Charlie Munger talked about in the Coca-Cola example above.

The next time you are looking at a company with a well-known consumer brand - or one that argues that its brand is valuable within a certain market niche - ask whether the company has a pricing power - the power to raise prices without impacting unit volume sales. If not, the brand may not be worth very much. If yes, like in case of Exide and Marico, the brand serves as a great source of economic moat.

Finally, remember that the big danger in a brand-based economic moat is that if the brand loses its appeal, the company will no longer be able to charge a premium price. For example, Colgate used to absolutely dominate the Indian toothpaste market over the past many years till consumers realized that they could get pretty much the same thing for a lower price from brands like Dabur and Pepsodent. And thus, the company seems to be gradually losing its pricing power, and thus its moat, though it will still be some time before the moat shrinks considerably (as the brand is still the strongest in the Indian toothpaste market).

The bottomline is that brands can create durable competitive advantages, but the popularity of the brand matters much less than whether it actually affects consumers' behavior.

If consumers will pay more for a product - or purchase it with regularity - solely because of the brand, you have strong evidence of a moat.

But there are plenty of well-known brands attached to products and companies that struggle to earn positive economic returns, and those you must be careful of.

Tip: A brand is the not the key to competitive advantage; the key is how the company uses the brand to generate added value. This you can find out by analyzing whether the company has been able to raise prices of its products in the past without compromising on volume sales, like I did for Marico and Exide above.

Identifying the 'Brand Moat'

How do you identify whether a brand has a moat?

In order to answer this question, you must answer - How would you (or a company) try to create a great brand, like say Coca-Cola or Asian Paints, or Exide, or Marico?

Consider Coca-Cola. However unhealthy a product it sells, the brand is associated with people being happy around the world. In fact, as the tagline along with the brand goes, happiness and Coke go together. For example, look at this video where the emotions of hope and happiness are aroused by Coke's advertisers. Now if you get unlimited amount of money and start selling, say Rola-Cola around the world, would you be able to have five billion people have a favourable image in their mind about Rola-Cola. You can't get it done. You are not going to touch the Coca-Cola brand. That is what you want to have in a business. That is the moat, which has just widened with years.

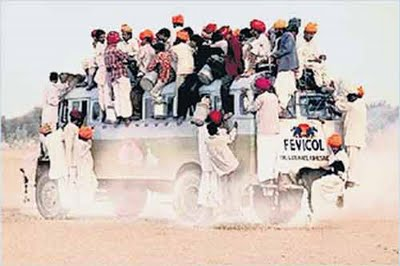

Look at India's Pidilite. If you have watched India's national television network Doordarshan years ago, you still remember this Fevicol ad.

Decades have passed, but Fevicol has not found its match in another industrial adhesive. This brand power has helped Pidilite define prices in its market, which has helped it grow its sales and profits at a strong pace. Investors have, of course benefited tremendously from Pidilite's invincible brand, which has constantly been associated with "strength and durability."

Consider McDonald's that was one of the first advertisers to really understand this. Decades ago, when their competitors were boasting about the size of their burgers or the thickness of their shakes, McDonald's was busy crafting emotional portraits of families enjoying moments of togetherness around a fast-food lunch.

Consumers could easily accept or reject the rational claims being made by competitors, but the poignant appeals pioneered by McDonald's changed the playing field. Instead of a binary "true or false" equation, these emotional slices of life were hard to argue against and easy to embrace.

You see, most people believe that the buying choices they make result from a rational analysis of available alternatives. In reality, however, emotions greatly influence and, in many cases, even determine our decisions.

In short, to create a sustainable moat through a brand, a company must associate it (the brand) with a set of positive emotions in its consumers. That's what triggers a "click-whirr" pattern in people to buy its products/services.

Click and the appropriate tape is activated (emotional appeal of a brand); whirr and out rolls the standard sequence of behaviour (purchasing decision of a buyer).

Companies that understand this can create sustainable brand moats - like a few examples I mentioned above. And this process is what you can use to identify businesses that benefit from this moat - businesses that arouse positive emotions in people.

This aspect of a brand can be analyzed…

In your real life, while encountering a business, if a salesperson smiles at you when you visit him/her at the end of a day, that business's moat has widened and if he/she snarls at you, its moat has narrowed.

A great moat is the total part of the product delivery. It is having everything associated with it say, Coca-Cola or Asian Paints and something pleasant happening. That is what business is all about, and you would come to know when you see it (the moat).

Moat #2: High Switching Costs

Switching costs are those one-time inconveniences or expenses a customer incurs in order to switch over from one product to another, and they can make for a very powerful moat.

Companies that make it tough for customers to switch to a competitor are in a position to increase prices year after year to deliver rising profits. Companies aim to create high switching costs in order to "lock in" customers. The more customers are locked in, the more likely a company can pass along added costs to them without risking customer loss to a competitor.

Do you remember the time you last changed your bank? Maybe never. Or the operating system that resides in your computer? Maybe never. Or your DTH set top box or Internet service provider? Maybe once in the last few years. Or your newspaper? Maybe once or twice in the last few years.

Now, do you remember when you last changed your fuel pump? Or the retail store from where you buy clothes? Maybe every time you go to a different fuel pump or a different retail store - depending on where you are and what discounts are on offer.

So, you see, some businesses have high switching costs, maybe due to hassle of switching (banks, DTH), or complexity (PC operating system) or habit (newspapers), which are valuable competitive advantages because a company can extract more money out of its customers if those customers are unlikely to move to a competitor. You find switching costs when the benefit of changing from Company A's product to Company B's product is smaller than the cost of doing so.

Till a few years back, India's mobile companies also benefited from the 'switching costs' advantage till mobile number portability enabled consumers to change their service providers while keeping their numbers.

Consider the case of Indian IT companies. Repeat business for them forms anywhere around 80-95% of their total revenues, suggesting that they benefit from the switching cost advantage, which is ultimately seen in their high margins.

Now, switching costs can be tough to identify because you often need to have a thorough understanding of a customer's experience - which can be hard if you're not the customer.

But this type of economic moat can be very powerful and long-lasting, so it's worth taking the time to seek it out.

Conclusion

Remember this - The best indicator of a moat or competitive advantage is a business's ability to increase prices without losing customers. I have shared a few examples in the lesson above.

Also, businesses that have pricing power typically have a few characteristics in common:

Now, the question is…

Where to Find Pricing Power Information

Look for pricing power information in the MD&A section of the annual report.

Prior to 2012 annual reports, you can find companies sharing their sales quantities from which you can calculate per unit pricing over the years (5-10 years).

Also, keep an eye out for important pricing power indicators such as:

In most cases, if a business has pricing power, it will disclose it. If the business does not disclose increasing prices, then it is highly probable the business does not have pricing power.